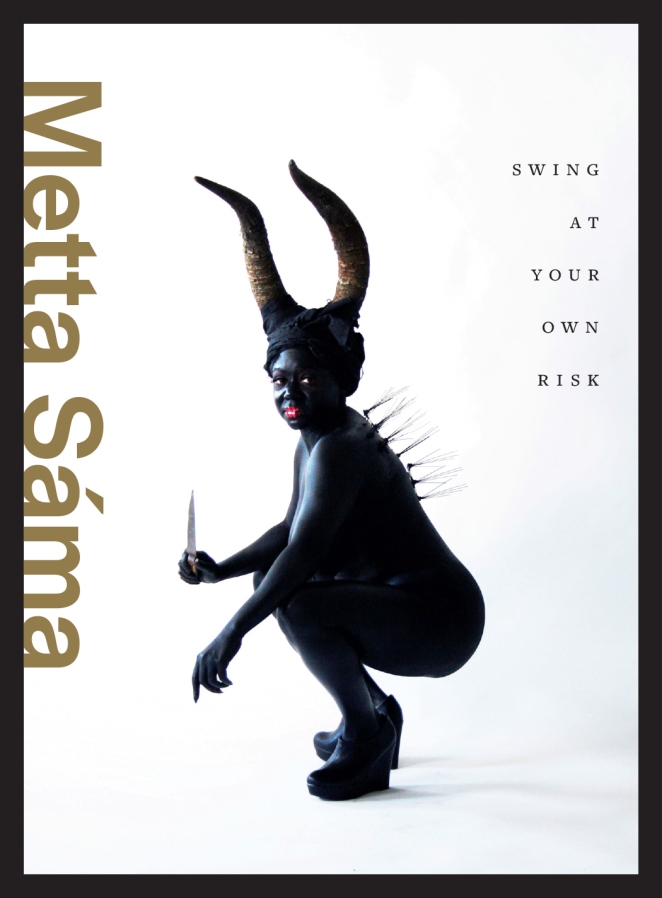

I’m so grateful for this thoughtful review by Alicia Wright over at Ploughshares blog. It’s not always easy to find readers who take the time to examine experimentation.

You can purchase SWING from Kelsey Street Press website or SPD Books.

I’m so grateful for this thoughtful review by Alicia Wright over at Ploughshares blog. It’s not always easy to find readers who take the time to examine experimentation.

You can purchase SWING from Kelsey Street Press website or SPD Books.

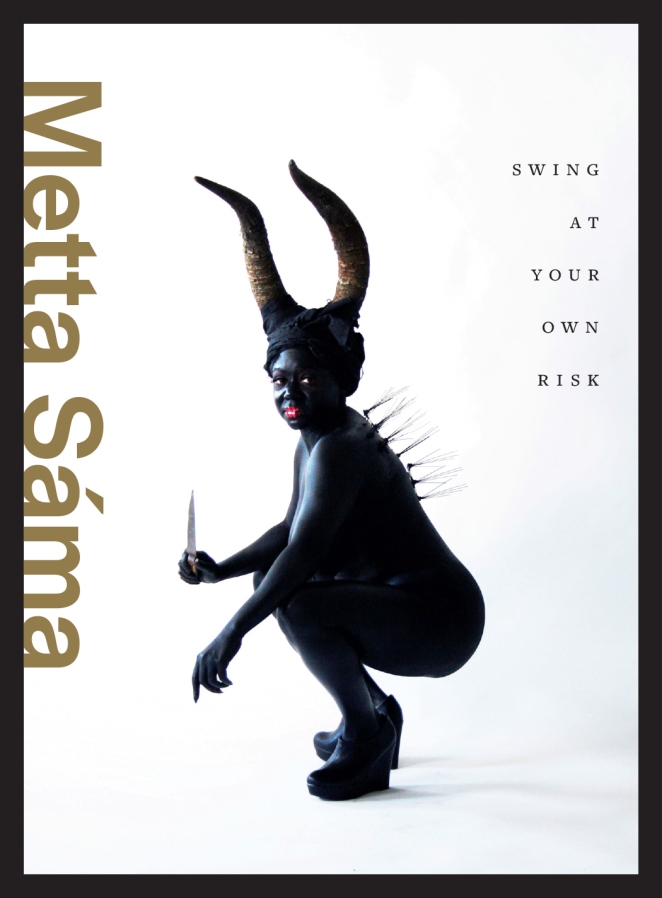

A decade and a half ago, when I decided on a whim to get a Masters in Afro American Literature at UW-Madison, I decided to write my thesis on Toni Morrison’s work. I’d first come to Morrison’s novels when I lived in Chattanooga, TN and was a student at UT-Chattanooga. A new bookstore had just opened, creating a space for used books, used cds/cassettes/albums and video-games. On my first visit to this store, I was completely overwhelmed at the sheer numbers of books. So, to mitigate my pressing sense of claustrophobia, I decided to focus on book spines. My eyes landed on The Bluest Eye & I was intrigued. What is this story about one eye? Is it a murder mystery? A detective story? Who is this Toni Morrison? I was perhaps 21 or 22, maybe 23, and I’d never heard of Toni Morrison. In fact, I had never really heard of any living Black writers or many non-living Black writers. I pulled the book from the shelf, studied the cover, and put it back, moving on until I hit the “B” section and found a new intriguing title, If Beale Street Could Talk. I didn’t know who James Baldwin was but I recalled a movie I’d seen, “The Women of Brewster Place”, and, confusing these two titles, purchased the book. Home, I couldn’t get the Morrison title out of my head or the odd cover, but Baldwin’s novel enticed me, so I spent the summer reading all of the novels of his that I could find at the used bookstore. And when I was done reading Baldwin, I was still haunted by that Morrison title. I raced back to the bookstore in search of The Bluest Eye.

It was a curious cover; a Black child holding a White porcelain doll; both the child and the doll appearing old, wizened. I want to say I read the short novel in one sitting, but who can read Morrison in one sitting? I didn’t devour Morrison’s sentences; I savoured them. “Quiet as its kept, there were no marigolds in the fall of 1941.”

Yesterday, I listened to a writer who was born in 1970, the year The Bluest Eye was published, say that she’d read the novel in high school. I was quite shocked and, honestly, jealous. Who were these Atlanta teachers who gave students a book by a living writer? By a Black writer, living or not? It wasn’t until 1997 that I read a Toni Morrison novel as part of a class assignment; this was after I had taken a course called African American Literature, in which we mostly read books by Black men, most of them not living. In a political science course on women and politics, we read Beloved. The teacher was White, all of my peers were White. Many of them boycotted the book after reading the first chapter, saying the teacher only selected it to make me, the one Black student, feel seen, which was absurd since the reading list was decided before students were enrolled. Most of them refused to show up after that first day, so the teacher sneakily moved the book to later on the schedule. The teacher cried in class while talking about the novel and apologized to me about slavery. I was still thinking about Sula, which I’d read after finishing The Bluest Eye and Song of Solomon, which I read after finishing Sula and Tar Baby, which I read after finishing Song of Solomon. I was intrigued by Morrison’s sentences, her paragraphs, her ability to make the past ALIVE and RELEVANT. I was thinking about my parents, how they had tried so hard to raise me as what I was–a Black child–and how I refused them, how their stories felt oppressive, how when they talked to me of the past I felt as if the clouds were cotton pressing down on me, pounds and pounds of cotton clouds choking me out; how I came, later, to understand that sensation as re-memory, how I came to understand that term, re-memory, by reading Beloved in that political science course, but how I wouldn’t know the term itself until I was a graduate student, three times over.

Violence. It was the violence that made me feel as if I were suffocating in my parents’ histories. The intense, perpetual, disregard of human life. Of animal life. I had a neighbor who had a dog named Smoky. The neighbor was a kid, a bit older than me but younger than my older siblings, so perhaps 12 or 13 when I was 9 or 10. The neighbor had trained his dog, had trained Smoky, to attack Black people. He’d sneer, “sic”, whenever he saw a Black person and Smoky would chase the Black person, snarling and threatening. The neighbor only did this with the younger Black children, of course. One day, I was riding my bike, going very fast, downhill, and about to make a hairpin turn, past Smoky’s house, when I saw the neighbor and then heard Smoky’s barking, felt his spit on my ankles. I had a really bad accident. Crashed my bike and surprisingly didn’t break any bones, didn’t die. The neighbor hovered over me, laughing, as I tried to disentangle myself from the bike, tried to get away from the barking, the snarling, the snickering. Violence.

As a very young child, I wanted to know everything about the other side of violence for my parents. Who were those adults who survived Jim Crow? Who dared to lust? Dared to love? Dared to procreate? Dared to sing & dance & laugh & be joyful, to become autodidacts, to be regional historians, who integrated a White neighborhood in 1978. My parents sacrificed their lives to offer their children access to resources that they had been denied; placing us in White neighborhoods so we could go to White schools where the students were provided with updated textbooks, had computer programming courses by 1985, had both college prep & AP courses, had pre-ACT & pre-SAT prep on Saturdays, had field trips and guidance counselors, school nurses and playgrounds; a tennis court.

Despite all of this luxury, all of this access, Smoky’s human was being raised by White adults to despise Black people. Smoky’s human had a sister named Beth. She was a year older than me, my sister’s age, but my sister didn’t like to play with Beth so Beth played with me. When I was maybe 7 and Beth maybe 8, she knocked on the door and asked me to come out to play. I wasn’t allowed to go out at that time, for whatever reason, and I told Beth. When I moved to close the door, Beth called me a nigger. My dad, hearing this, invited Beth to our weekly Black History classes. Love. Beth came for one or two classes but afterwards, she stopped coming by altogether. When I later saw her, she said her mother didn’t want her playing with niggers.

Morrison’s novels showed me the starburst patterns of racial violence. She says in an interview that she wanted to write a novel that examined the question of self-loathing. What were the conditions that made a Black child loathe herself? I understand this question and the violence that undergirds the responses. But it wasn’t until I read The Bluest Eye that I was able to point at so many racial violences, including the ones we take for granted–billboards featuring “beautiful” White women; candy wrappers featuring “cute” White children, and the ways in which these violences were not the other side of Love, but completely antithetical to Love. In the South, we hear so often how Confederate-flag flying White people are not racists, but just people who Love themselves and their culture; how it’s Love that drives the cross in the ground; Love that sets fire to that cross; Love that holds the rifle; Love that pulls the trigger; Love that places a noose around a Black person’s neck; Love that hangs and maims and destroys. But in reality, its racial violence that, for example, kept Polly (Pauline Breedlove) from having access to, say, art education. Violence that kept Polly from becoming an interior designer or visual artist. Racial violence is America.

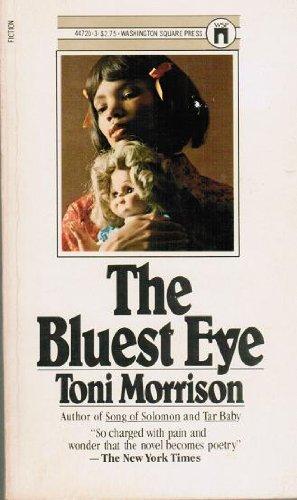

By the time I decided to get yet another Masters degree, I had read all of Morrison’s published novels. I read Jazz twice before I was able to appreciate it (and was only able to appreciate it after I spent a summer listening to jazz music and educating myself on jazz music). As a student in the Afro American Studies Program, I went a step further with Morrison: I began to read criticism about her work, interviews of her discussing her work. I would go on to write my own critical responses to her work, deciding, while writing my thesis, that part of what made Morrison’s work special and difficult is that her narrators are intellectuals. They analyze the story that they’re telling as they’re telling it. It’s like reading a dissertation and a story all at once. What could I say about her work that she herself wasn’t already saying in the work? And how had she learned to write in this way? Eventually, I abandoned that thesis project and instead wrote a chapter on Sula, but I continued to read Morrison, to re-read Morrison’s interviews, to share her work with students. (And, to be honest, the first time I read Sula and all the times afterwards, I thought: on Halloween I will dress up as Sula, because, really, I wanted to be Sula. A student, knowing how much I loved Sula, painted a picture for me, of Sula returning home and the blackbirds announcing her return.)

“Recitatif” is easily, for me, the most brilliant short story I’ve ever read. Its manipulations, its focus on the reader, on tapping into readerly bias and prejudice and stereotypes; all of it is so compelling. And, no, it’s not the best written story; but it’s the best story. Who has read that story and is still not making an argument about who is who; which person is Black and which is White. And why, in a story that refuses us that certainty, does it matter? Why are we so compelled to fix that race.

I love Toni Morrison’s writing. I love what Toni Morrison’s writing has done for me, individually, as an intellectual, as a scholar, as an advocate, as an activist, as a writer, as an educator. I love knowing that Morrison’s mother’s name is a city, just as my birth name is a city; that our names were chosen in the same way, picked from the Bible, that neither of us like those names. And yet, that holding the name of a city, an ancient city, places a kind of responsibility on us. A kind of birthright or birthmark: to hold the name of a city is to hold people, language, food, beliefs, practices, knowledge, songs, dances, pleasures and delights, wars and ravishments, to hold dream and vision and to make space for many to build futures. Morrison’s work, even the work set in the past, builds futures. Yes, she’s now transitioning to another space, another dimension, but her work is here, always. Thank you, Toni Morrison.

Author’s note: The title of this piece comes from a Toni Morrison interview Emma Brockes for The Guardian.

A couple of days ago, two white people were arrested for vandalizing a 1932-erected Confederate statue. The papers don’t identify the vandals as white, of course, but a later post includes their photographs. They threw red paint on the statue, located in White Point Park, intended to depict, I reckon, blood. We’ve learned that many of these 1920s-1930s statues were commissioned by the United Daughters of the Confederacy, a group that has a museum here, located in the old Slave’s Market (now called City Market). In a statement made concerning the push to have these statues removed, the UDC remark:

The United Daughters of the Confederacy totally denounces any individual or group that promotes racial divisiveness or white supremacy. And we call on these people to cease using Confederate symbols for their abhorrent and reprehensible purposes.

We are saddened that some people find anything connected with the Confederacy to be offensive. Our Confederate ancestors were and are Americans. We as an Organization do not sit in judgment of them nor do we impose the standards of the 21st century on these Americans of the 19th century.

Statements such as these, contradictory at best, illustrate the ways in which racial divisions in the U.S. continue to be swept under the carpet, pushed into the closet, and masked. One cannot both denounce white supremacy and insist on memorializing the very hallmarks of U.S. white supremacy.

Here in Charleston, during a carriage tour, our guide, Rivers, very clearly took to heart the name of the company he works for: “Old South”. Rivers, who seems to want a career as a stand-up comic or comedic actor, affected an attitude of the Southern good ole boy, a charming, funny, self-deprecating sort, who loves his drink, his god, and most of all, his Charleston (despite not being from around these here parts). Rivers spoke in a “we” as he offered up a brief history of the best white men Charleston has to offer. At some point, I thought I had drifted away and not heard who this “we” referenced, so I interrupted his speech and asked “Who is this we you keep referring to?”. He replied, “The Brits. Did I not say that?”. Did I mention I was the only person of color on the tour? Needless to say, the White passengers shuffled in their seats when I raised my question; the White couple sitting next to me, already irritated that they had to share their 4-person bench with someone other than themselves, were visibly irritated with me (the man rolled his eyes and the woman turned up her chin at me).

It’s difficult going on these kinds of U.S. Southern tours. In a Southwestern river tour in San Antonio, the same kind of glorification of the U.S. went on. Thankfully, at that time, I was with two friends: one a white guy from Florida and the other a Nicaraguan woman from California. My Californian friend and I had each other to complain to, to throw comments at the tour guide, challenging his faithfulness to a U.S. that destroyed a nation, killed its inhabitants, stole its land, and lived to tell the tale by controlling the narrative.

Rivers’s controlled narrative included U.S. Southern slavery as an anecdotal story of U.S. white male survivalism. I summarize: the poor white British came here and were attacked by these unsavory insects called mosquitoes and contracted this horrible hot weather disease called malaria and let me tell you, if we can beat malaria we can beat anything! Even a writer for the NY Times, Christian L. Wright, upheld this narrative of the U.S. South as utterly charming.

The world is in love with Charleston: the antebellum mansions, the cobblestone streets, the mild climate that might bring 70-degree days in February, the scent of tea olive trees that floats in the air, the orchestra of church bells that crescendoes on Sunday morning, the day drinking. It’s a genteel and mannerly place with its complex history in plain view: stone hitching posts from the Revolutionary period, the Old Slave Mart on Chalmers Street that’s now a museum. The belle of South Carolina has also become a cultural hotbed and gastro-magnet — with more restaurants than there are pelicans in the harbor. The tourists — more than five million in 2015 — tend to swarm the recently renovated City Market and pile into horse-drawn carriages, which leaves plenty of room to explore the city’s lesser-known charms.

Rivers mentioned slavery once, by correcting any assumptions that we may have that the City Market, which he said, has been incorrectly called the Slave Market, leading people to believe that slaves were sold in the market, was actually a safe place purchased by Pinckney to establish a farmer’s market for slaves. He quickly gave this history in order to get to his real point about City Market: that the Daughters of the Confederacy had a museum in the market and had really wonderful relics in there and that we really should go and visit the museum. He did slow down, however, to remind us that black people are filthy. I paraphrase: the people sold fish and threw their fish guts into the streets which caused the whole place to really stink! But the city does provide animals that do a great job in cleaning up street filth. They’re called rats. But these rats didn’t clean up the streets. They got fat and ended up near the river, where they became known as river dogs. But, what the rats didn’t tend to, the vultures got.

At the start of the tour, Rivers pointed out three young black boys who were making sweetgrass roses. Rivers said, and here I quote directly, “You’ll see boys selling these roses around. They’ll tell you they’re for basketball camps. They are NOT. It’s just a scam, guys.” Anyone with a passing knowledge of the Gullah people of South Carolina know that sweetgrass weaving is a special skill that the Gullah people have held onto, while most of their history has been taken from them.

It’s difficult being in the U.S. South. I’m sitting in a coffeeshop in which I’m the only black person here who is not working. Dozens of lounging white people, sipping coffee, shooting the breeze with their friends, booking trips to Rome, overseeing summer private tutoring sessions for their children, reading books, reading the newspaper. It’s late morning. At the restaurants along E. Bay St, the diners were primarily white (and likely tourists), the waitstaff primarily white, the kitchen staff overwhelmingly black. On Meeting St, older black women sat in patches of shade, weaving sweetgrass into baskets that they’ll sell for less than they’re worth, baskets that would fetch a pretty dollar if a white person had them in their shops. In the City Market, where, according to Rivers and the websites, slaves were provided a space to sell food, the booths were overwhelmingly held by white people hawking coffee beans, infinity scarves, tchotchkes and t-shirts. The majority of the black vendors sell sweetgrass baskets, an homage of their ancestral past, their present preserved.

Rivers says there is a city ordinance that protects the exterior of any building that is 75 years old or older. He says this with pride when we’re in the sections of Charleston that he both derides because of its wealth–letting us in on the Charleston code for these sections of town: SNOB (Slightly North of Broad) and SOB (South of Broad)–while also confessing that he, too, wants wealth enough to live in SOB. When we’re in areas of Charleston that are neither SNOB nor SOB, Rivers’s contempt for the 75-year exterior housing ordinance is apparent: “To your left you’ll see the ugliest house in all of Charleston & do you know why it’s allowed to stay this ugly? Because of Charleston’s law that protects houses that are 75-years old or older.” He shakes his head in a melodramatic gesture and waxes non-poetically about the shame of preserving such hideousness amongst such splendors (the house was quite close to the house of Nathaniel Russell, a home that Rivers praised for its ostentatious show of interior wealth).

Like many U.S. Southern cities, whiteness is worth preserving and blackness is to be ignored, avoided, erased, scolded. Indigenous americans are completely out-of-the-picture.

One of the things that I appreciated about traveling in México and traveling in Costa Rica, was the ways in which museums and historical sites refused to be kind to the colonialists. Colonialists destroyed their cultures: their languages, spiritual practices, foods, educations, lands. In the U.S., we all live so close together that we tiptoe around white pillagers, working overtime to protect their feelings, their egos. I’m still in search of the U.S. South that has more Native American wealth, black wealth, Mexican wealth than white wealth. A U.S. South that punishes its white people for yes, their ancestors abuses, atrocities that have provided them, in this current time, the luxury of relaxation, the same luxury their forefathers appreciated, the luxury to lounge. After all, in the City Center of Charleston, there are no young white boys hawking their wares, no elderly white women finding patches of shade to stitch their quilts that they hope to sell.

Rivers interfered with the black sweetgrass weavers ability to sell their wares. For every white person who rides in Rivers’s carriage learns that these weavers are degenerates that the city, for some bizarre reason, tolerates.

On the upside, Frank, the horse, refused to be silenced, neighing and trotting in the streets, instead of quietly, submissively, walking under someone else’s orders.

This morning I made several stops–the library, thrift stores, 2nd hand stores–dropping off items my rapidly growing toddler no longer needs. It’s March & difficult to be in this month without thinking of the twins that spontaneously aborted themselves from my body 26 years ago. For years, after the miscarriage, I used the technical terms that the doctor’s used with me: spontaneous abortion, S & C (Suction & Curettage). I was 20 years old when my mother looked me in the face, told me my dad had been dreaming of fish again, a whale this time, told me that I was pregnant. The youngest of her children, I wanted to deflect, to not have to deal with my mother realizing that her baby girl was having sex; I wanted to stall for time, to not have to deal with the fact that whenever my dad dreamed of fish, one of us daughters was pregnant, time to think about irony, how my boyfriend and I had spent nearly a year having unprotected sex and now that we were using condoms and I was on birth control pills, that I, according to my mom’s dream analysis, was pregnant. Mostly, I didn’t want to think about what it would mean for me, a 20-year old achiever, the first in my entire line to likely graduate college, to be pregnant with her 19-year old boyfriend who was already someone’s father.

A dreamer with a serious practical nature, I made two appointments: one at the planned parenthood clinic, where I could ponder an abortion while waiting for pregnancy test results, and one at my mom’s gynecologist, where I could ponder life as a mother while waiting for a second result from a pregnancy test. My boyfriend accompanied me on both trips, talking both times about how happy he was, how he wanted me to meet his daughter’s mother, what a lovely, large happy family we would be. I was thinking of how I would explain to my friends that my sorta kinda cousin and I were expecting a child together, how I was going to explain to my high school best friend that that guy she met at graduation, the one I said was my cousin, the one whose smile stopped her in her track, whose presence had her so nervous that she asked me to ask him to go out with her, that guy, that’s the guy I was now pregnant with. Planned parenthood confirmed it. At my mother’s gynecologist, I told the doctor all about how me and this guy, my boyfriend, had met when we were just kids, how he’d flirted and my mom said it was okay for him to have our number, how we discovered pretty quickly that we were sorta kinda cousins, how we lost touch for years, how we ran into each other at graduation, exchanged numbers, went on a long walk, in which I talked up my best friend, in which he stopped me and said “I didn’t come here for her, though” and we kissed and have been kissing and then some since. The doctor said that was all very sweet and that we needed to not do missionary style sex anymore because his penis was knocking into my cervix and causing swelling and my boyfriend was hopping around and I thought he needed to pee but really he just couldn’t hold his tongue anymore. He proposed. In the gynecologist’s office, while I was half naked and my mother’s doctor was there, he proposed and the nurse came in and told us that we were, in fact, pregnant.

A few months later, my obstetrician told me that the baby was spontaneously aborting and that we needed to make an appointment to extract it. At the hospital, after the S & C, the doctor who was not my regular doctor told me I must have had twins, there was twice the amount of tissue there should have been at 20 weeks. It was October. I’d unenrolled from one college and enrolled in the college in my home city, the city that nearly my entire family lived in, the city that I changed my aspirations to mere accomplishments. I wouldn’t be lawyer or a photojournalist or a doctor after all. I’d be a nurse. I wasn’t going to be free, I was going to be a wife. I was going to be a wife and a mother and a step-mother. I was going to be a nurse because nursing school was only 5 years and by the time I was out of nursing school, my child would be in first-grade and my boyfriend could then go to college and accomplish something. And by the time the child was 18, I could go back to college and be an achiever again. I had it all figured out. The child was due in March. We learned of the pregnancy in June. By September, everything was falling apart again. The doctor was telling me that something was not right with the pregnancy. He couldn’t see the baby even with a vaginal probe. He sent me for an ultrasound then 24-hours of blood tests then he finally told us: the baby is spontaneously aborting, he said, we have to extract it, he said, you don’t want this to turn into a full miscarriage, he said.

I never wanted to be pregnant at 20 but I’d given in to it. Being pregnant. Becoming a mom. After the S & C, the stand-in doctor told me I must have an under-developed cervix, that a spontaneous abortion at my age was unusual. I was stuck in the word “twins”. My father’s father was a twin and we’d all been wondering who would have the twins. If the fetus was not one but two, it was me, and I’d let my family down again. First I got pregnant at 20, gave up my scholarship, came home, then I couldn’t even properly stay pregnant with the first twins in two generations. March was waiting for me, poking at me, taunting me, throwing pictures of a swollen fire-red underdeveloped cervix in my face. Every March for 20 years, I mourned those fetuses, grieved that disappointment, cursed the month and everything it stood for, found others who had losses in March–grandmothers, fathers, mothers. March was a month of taking.

One March, not too long ago, the pull was so intense, it made its way into April, where I nearly ended myself. For decades, I thought of the phrase “spontaneous abortion” and tried to make light of it. Wrote poems about it, learned to feel proud of my fetuses for deciding, for themselves, that they didn’t want this world.

Who would they be, though. I wonder so often. & sometimes I’m so happy that they ended themselves as they were making themselves, that they missed this ever erupting world. I’m happy that I don’t have to give them the black talk, the please don’t get killed by the police talk, the of course you will be overlooked/underappreciated/undervalued talk, the you don’t have to be strong all of the time black people have weaknesses too talk, and on and on. And of course, had they chosen to carry on, to stay with me, I wouldn’t have made my way to poetry, I wouldn’t have ended up in this city I despise, I wouldn’t have met this child who I get to parent. I wouldn’t have this book to share with you.

It’s March. And I miss them. I never met them. I always wanted them. They would be 26 years old and I know nothing about them. I refuse to imagine who they would be now, these fetuses that chose to not enter this world. They deserve their own tales, their own imagined futures. And my face or their dad’s face, they would have had one damned dazzling smile. And March would have to just fuck off.

Skip to 28:31 to watch the phenomenal Jaki Shelton Green get crowned & begin her speech! ~

Here is part 2 of the Poetry Mini Interviews in which I shout out a whole lot of poets including the poet whose lines graced pens my father had made when I was a wee lad. Continue reading

Thomas Whyte has this great interview series in which artists are given an opportunity to respond to up to five questions. These responses are posted over at Poetry Mini Interviews and only one response per week is posted. Here’s my first response.

Thanks so much to Tc Tolbert for including me in this monthlong series of poems by queer, gender variant, transgender, lgbtia poets.

This social media black-out of women happened last year for women in India. The article posted here shares some competing thoughts about it.

When I was an early twenties student in Chattanooga, I participated in the very first National Day of Silence, 1996. I thought it was pretty exciting. Because I was in my early 20s and I hadn’t really thought, deeply, about what it means for LBGTQIA voices to be self-silenced, to be unheard, to be, basically, in the same position the voices had always been in: the background. Yes, LGBTQIA students spoke in class; I spoke in class, frequently, yet, my “status” as queer was never discussed/seen. I was simply a student who was speaking. Not speaking invalidated my existence, but in my early 20s, I didn’t know that. I do recall feeling strangely strangled, however, and feeling more devoted to the cause than to myself. My sense of loyalty radically erasing my individuality.

I found power in the national walk-out of women last year, particularly as so many institutions of higher learning, including the one where I teach, a women’s college, punished women for not showing up to work on that day. You see, there’s something to be said about not showing up to labor, the deep significance of not providing service to those who have oppressed, suppressed, repressed us and who will continue to do so, unless they are forced to face the reality of a day without women. I wondered, however, how many women walked out of their domestic labor lives.

This blacking out of an image on social media fails, for me, significantly, in the way that the National Day of Silence fails, for me, significantly. I’d love to see more campaigns that advocate for women, queer people (LGBTQIA), people of color, differently abled people, financially poor people, to rise in collective power instead of being collectively erased. We do, after all, live in a world in which women already feel invalidated, so much so that we invalidate women we see as less powerful than us. Searching desperately for any modicum of power, of visibility.

Of course, you will do you and I’m not asking you to not do you. But there are enough of these calls to be invisible in my inbox, calls by White women, for a woman of color to be invisible, that I feel compelled to explain why my visibility is the most threatening, most dangerous, most vital reality in many a White life.

& thank you to Allyson Kapin for this reminder of the recent call to action.